Defining the Core Problem The double spending Issue in Digital Cash

In customary cash transactions,a physical bill can only be in one place at a time,which naturally prevents it from being spent twice. Digital money, however, is just data, and data can be copied effortlessly. This opens the door to a specific vulnerability: a user could attempt to send the same digital token to multiple recipients, effectively creating value out of nothing. legacy digital payment systems solve this by relying on a central authority-typically a bank or payment processor-to keep a master ledger and verify that each unit of value is only used once. While this works, it concentrates power, introduces single points of failure, and requires users to place blind trust in an intermediary.

bitcoin’s white paper directly confronts this vulnerability by asking whether it is indeed possible to prevent duplicate spending without that central gatekeeper. The challenge is not simply tracking balances, but getting a global network of independent participants-who may not trust each other-to agree on which transactions are valid and which came first when there is a conflict. In other words, the system needs a publicly verifiable, tamper-resistant history of who paid whom and in what order. To be credible, this history must be resistant to manipulation, even by powerful actors, and must be understandable enough that ordinary participants can independently verify it.

At the heart of the solution is a combination of cryptography, economic incentives, and network consensus that makes double spending economically irrational and computationally impractical. Instead of deferring to a bank, the network relies on nodes that validate transactions and miners that compete to add them to a shared ledger, forming a chain of time-stamped blocks. Each block builds on the last, making past records increasingly costly to rewrite. This design transforms what was once a purely technical flaw-easy duplication of digital data-into a problem addressed through a mix of protocol rules and game theory. Key contrasts between conventional digital cash and bitcoin’s approach include:

- Control: From centralized ledgers to distributed verification.

- trust model: From trusting institutions to trusting open-source rules.

- Security: From legal recourse to cryptographic and economic guarantees.

| Aspect | Traditional Digital Cash | bitcoin’s Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Double-Spend Protection | Central ledger checks | Decentralized consensus |

| Authority | Bank or processor | Open network of nodes |

| Failure Point | Single, centralized | Distributed, resilient |

How bitcoin Uses Decentralization and Proof of Work to Remove Trusted Intermediaries

In the system described by the white paper, control is pushed to the edges of the network rather of being concentrated in a single company or bank. Every full node independently verifies transactions using the same transparent rules, and no participant is granted special privileges. This shared rulebook-bitcoin’s consensus protocol-ensures that a valid transaction looks the same to everyone, whether it’s processed in New York or Nairobi. because anyone can join, leave, or rejoin the network without asking permission, the ledger’s integrity does not depend on a central gatekeeper’s honesty or solvency.

Proof of Work (PoW) adds a layer of economic and computational cost to the process of proposing new blocks. Miners compete to solve a hard mathematical puzzle, proving they have invested real resources (electricity and hardware) before they can append a block to the blockchain. The network then automatically accepts the longest valid chain as the authoritative history. This mechanism makes it extremely expensive to rewrite past transactions,while leaving verification cheap and simple for ordinary nodes. In effect, pow turns raw energy into a security budget that defends the ledger against fraud and censorship.

By combining distributed verification with PoW, the system replaces institutional trust with verifiable computation and open consensus. Instead of asking users to trust a familiar brand or regulated institution, it offers transparent, predictable rules enforced by code. Key implications include:

- No account freezes: Valid transactions cannot be arbitrarily blocked by a central party.

- Borderless access: Anyone with an internet connection can participate without a bank account.

- Auditability: The entire history is publicly visible and independently checkable.

- Resilience: Failure or capture of individual nodes does not halt the system.

| Traditional System | bitcoin Approach |

|---|---|

| Bank or processor validates | Network nodes validate |

| Policy-based approval | Rule-based consensus |

| Trust in institutions | Trust in math and code |

| Closed ledgers | Public blockchain |

Understanding the Blockchain Data Structure and Why Immutability Matters

Imagine a public ledger where every page is permanently glued to the previous one, and everyone can see each page at any time. That’s essentially how blocks function: each block contains a list of validated transactions, a timestamp, a reference (hash) to the previous block, and a unique cryptographic fingerprint of its own. Because a block’s hash is calculated from its contents and the previous block’s hash, the entire history of the chain becomes mathematically linked. Change one character in an old transaction and the altered block’s hash changes, breaking the chain of references and revealing the tampering instantly.

This design makes certain core properties possible:

- Clarity - Anyone can independently verify transactions from the very first block.

- Consistency – All honest nodes converge on the same ordered history of events.

- Traceability – Coins can be followed from creation to current ownership.

- Security by structure – Attacks must rewrite not just one record, but an entire sequence of linked blocks.

| Feature | What It Means | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|

| Hash Linking | Each block points to the previous | Makes history tamper-evident |

| Proof-of-Work | Costly puzzles secure each block | Altering data becomes economically prohibitive |

| Distributed Copies | Ledger exists on thousands of nodes | no single party can quietly rewrite records |

Immutability is not just a philosophical ideal; it’s the mechanism that makes a peer-to-peer cash system practical. In traditional finance, trust is concentrated in central authorities that can edit databases at will. Hear, trust is shifted to a combination of cryptography, economic incentives, and game theory. To rewrite past transactions, an attacker would need to control enormous computational power and race against the honest network to rebuild block after block faster than everyone else. The cost and visibility of such an attempt make it irrational in most scenarios, which is exactly the point: by making history extremely hard and expensive to change, the system gives users strong guarantees that once a payment is buried under several blocks, it is effectively final.

Incentives and game Theory How Mining rewards Secure the Network

bitcoin quietly turns the entire network into a strategic game where rational players are nudged to behave honestly. Rather of trusting a central authority, the system assumes that participants act in their own economic self‑interest.By tying block rewards and transaction fees directly to valid block creation, the protocol makes it far more profitable to follow the rules than to attack them. This is not accidental; it is a deliberate application of game theory, where the ”winning strategy” for most players is to support the network’s security and integrity.

Miners commit energy, hardware, and time in a competitive race to find the next valid block. The design ensures that:

- Honest mining earns consistent, predictable rewards over time.

- Cheating requires enormous cost with uncertain or short‑lived gain.

- Coordination around the longest valid chain becomes the dominant strategy.

- Reputation and sunk cost discourage miners from undermining the system they depend on.

Because rewards are paid only for blocks accepted by the majority, any attempt to double‑spend or rewrite history demands majority hash power and risks losing both block rewards and fees if the attack fails.

| strategy | Short-Term Incentive | Long-term outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Follow the rules | Earn block rewards and fees | Stable, recurring profit |

| Attempt a double spend | Potential one-time gain | High cost, likely loss of rewards |

| Drop out of mining | No risk, no energy cost | No share in future rewards |

This incentives structure creates what game theorists call a Nash equilibrium: given the rules and the behavior of others, no rational miner can improve their expected payoff by unilaterally deviating from honest behavior. Mining rewards, difficulty adjustment, and chain selection by the longest valid proof‑of‑work chain combine to transform conflicting self‑interests into a robust security mechanism.The result is a system where economic pressure aligns with protocol compliance, making integrity not just a moral choice but the most profitable one.

Transaction Validation From Digital Signatures to Network Consensus

In bitcoin, every coin transfer begins with a simple yet powerful cryptographic ritual. The owner uses a private key to generate a digital signature, authorizing the spending of specific outputs and binding them to the recipient’s public key. This signature proves,mathematically,that the spender is entitled to move those coins without ever revealing their private key. On its own, however, a valid signature only certifies that a specific key pair approved the transaction; it says nothing about whether the same coins were already spent elsewhere in the network.

To solve that, bitcoin links individual signatures to a global, shared transaction history.Nodes assemble signed transactions into blocks and then collectively decide which block becomes part of the growing chain. Rather of relying on a central authority to confirm who spent what,the system uses a competitive process-proof-of-work mining-to determine which version of the ledger is accepted. The longest valid chain, built by expending measurable computational effort, becomes the reference everyone follows, making it economically and practically infeasible to rewrite history beyond a certain depth.

From the user’s perspective, the process of a transaction becoming “real” can be summarized as:

- Creation: user crafts a transaction, referencing previous outputs as inputs.

- Signing: Inputs are signed with the corresponding private keys.

- Broadcast: The signed transaction is sent to the peer-to-peer network.

- Verification: Nodes validate syntax, signatures, and available balances.

- Inclusion: Miners include valid transactions in a block.

- Confirmation: The block gains depth as new blocks are added on top.

| Stage | Key Check | Network Role |

|---|---|---|

| Signature | Is the spender authorized? | Wallet & full nodes |

| Validation | Does it follow consensus rules? | Full nodes |

| Consensus | Which history is canonical? | Miners & all nodes |

Practical Takeaways Applying the White Paper’s Principles to Modern Crypto Projects

Modern builders can honour the original design by starting with trust-minimized architectures rather of bolting on decentralization later. That means reducing reliance on privileged admins,designing protocols so users keep control of their keys,and making consensus rules transparent and verifiable. In practice, teams should document exactly who can upgrade contracts, pause the system, or access treasuries, and then work systematically to push those powers from single entities to distributed mechanisms over time.

- Favor simple, auditable rules over opaque complexity.

- Minimize required trust in founders, sequencers, and oracles.

- Default to on-chain verification where possible.

- Design for adversarial environments, not ideal users.

| White Paper Principle | Modern Crypto Implementation |

|---|---|

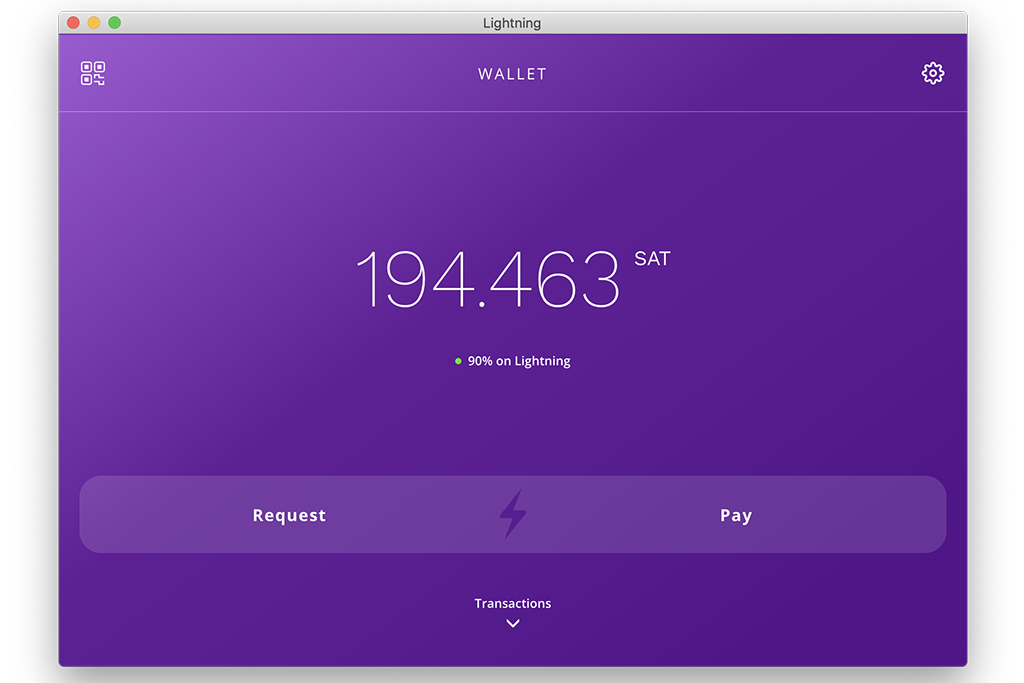

| Peer-to-peer value transfer | Non-custodial wallets and DEXs |

| Consensus without central authority | Public, permissionless validators |

| Proof-based security | Merkle proofs, fraud proofs, ZK proofs |

| Fixed, predictable rules | Transparent tokenomics and upgrade paths |

Security and incentive design should reflect the original insight that rational actors respond to cost and reward, not to mission statements or branding. Token models need hard constraints on supply and issuance, clear alignment between users, validators, and developers, and mechanisms that make attacks economically unattractive. This includes stress-testing protocols against governance capture,ensuring liquidity isn’t controlled by a few insiders,and treating censorship resistance as a measurable property-not a marketing claim-by analyzing node distribution,client diversity,and upgrade processes.