Photo by on

Photo by on

Economic concepts are appearing more and more in the literature on crypto-currencies. One that has been made quite popular currently by ()and () is the Quantity Theory of Money (Quantity Theory). Although the Quantity Theory can be extremely useful for analyzing and understanding economies that use tokens, some of the ways in which it is being used are not correct. The purpose of this post is to set forth the correct way to use the Quantity Theory in token economies.

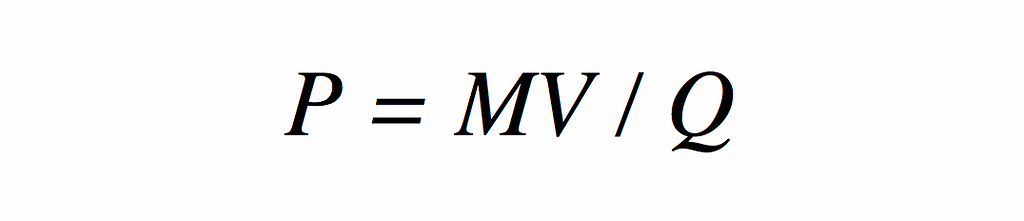

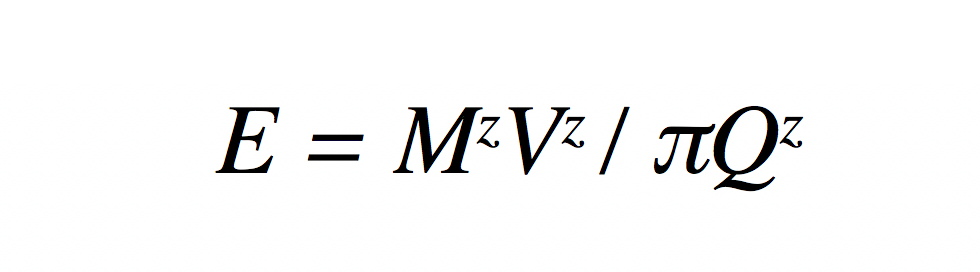

The most common version of the Quantity Theory as it is used in the economics literature was put forth by the noted Yale University economist Irving Fisher in his book published in 1911. Fisher’s version of the Quantity Theory of Money starts with the propositions that the output in an economy is purchased with money and that a unit of money can be spent more than once during a period. Putting these two propositions together yields the Quantity Theory of Money:

Equation (1) states that total money expenditures MV in a period is equal to the total nominal value of output in an economy in a period, PQ.

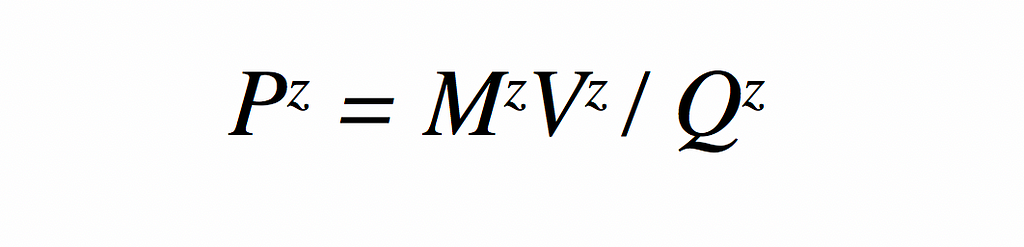

The correct way to use Quantity Theory of Money for tokens is to apply (1) to the project economy in which the tokens are used. Consider a project economy that uses a token that I will call ZZZ. Applying (1) to that economy yields:

Two important points of note:

Velocity, Vz, is the number of times a unit of ZZZ is spent on the output of the project during a period. Velocity is NOT the number of times a unit of ZZZ is spent on USD or some other currency.PZ is the price of a unit of Qz in terms of ZZZ. It is not the price of USD in terms of ZZZ. For (2) to hold, the units on both sides of the equation must be the same. This will be the case only if Pz is the price of a unit of Qz in terms of ZZZ.

Point (2) above is extremely important. Failing to satisfy it can lead to the Quantity Theory of Money being misused when applied to tokens.

Two Correct Applications

One way in which the Quantity Theory has been used in the economics literature is to obtain a relationship between the money supply and the price level. This relationship is obtained by moving some terms around in (1) to get:

This approach takes M, Q, and V as given.

Applying this to the project economy yields:

Equation (4) states that the price level in the project economy is a function of the quantity of ZZZ outstanding, the velocity of those tokens as they are spent on project output, and the project’s output.

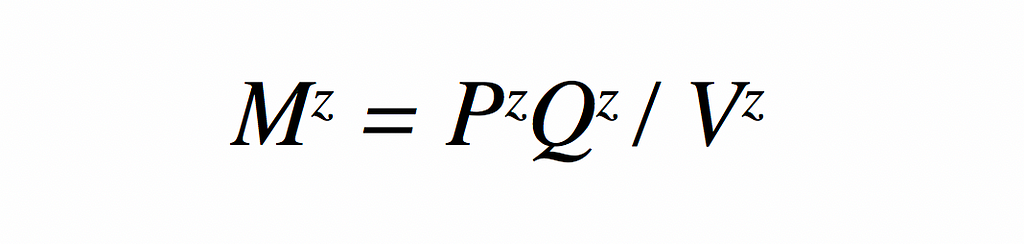

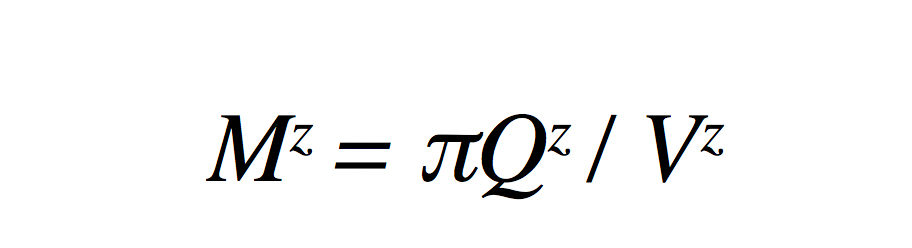

The second correct application of the Quantity Theory of Tokens is to rewrite (1) as:

Equation (5) gives the quantity of tokens that would have to supplied to the project economy to support total expenditures in terms of ZZZ on project output without a change in the quantity of output or the price the project’s output being required.

Two Incorrect Applications

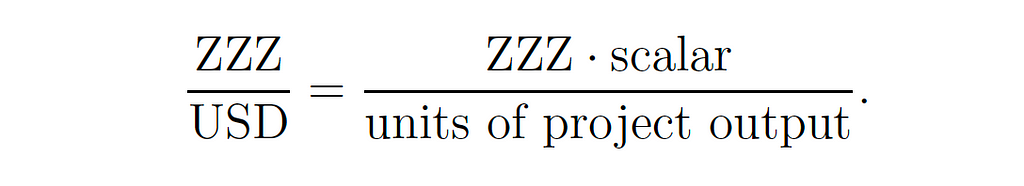

One incorrect application of the Quantity Theory of Tokens superficially looks like equation (3), but is actually quite different and incorrect. The crypto literature some times uses the equation that looks like the Quantity Theory to price ZZZ in terms of USD:

where E is the USD price of the token ( ZZZ / USD).

Equation (6) is not a correct use of the Quantity Theory because two sides of (6) are in different units. When (6) is written in terms of the units on the two sides of the equation, one obtains:

For (6) to be a correct specification, the units on both sides of the equation have to be the same as is the case with (1). However, USD does not appear anywhere on the right hand side of (7).

As an aside, note if the project prices its output in terms of USD, then the units problem mentioned above does not arise and an equation similar to (4) can be used. Let π be the USD price of Qz. Then the equation

has the same units on both sides the equation and can be used to price ZZZ in terms of USD. Of course, this raises the question of what the role tokens are playing in the project economy if the entire output is being sold for USD.

The second incorrect application of the Quantity Theory of Money is to rewrite (1) as

The difference between equations (5) and (9) is that (5) states the nominal value of output (PzQz) in terms of ZZZ, the project economy’s output, where (9) states the nominal value (πQz) in terms of USD. Once again, the units problem arises. The units on the left side of (9) are units of ZZZ, whereas the units on the right hand size are USD. Not correct.

The bottom line: To use the Quantity Theory correctly the price has to be the right one.

Aside: If the project does not price its output in USD and only prices it in ZZZ, then one approach the pricing question would be to use economic models like those used to determine the exchange rate between national currencies. One such model is purchasing power parity. The idea behind this model is that arbitrage would drive the exchange rate between two currencies to the point at which the price of a good is the same regardless of the currency with which it is being purchased. (If the good is being purchased in different locations and the currency used is location specific, then adjustments have to made for transportation, tariff and other such costs. I ignore such costs here as they are not relevant for this discussion.) In other words, purchasing power parity implies E = P(z) / P(usd), where P(usd) is the USD price of the project good. That is, and this is critically important, P(usd) is NOT the U.S. price level but is the price of the project good in terms of USD. Since Pusd is unobservable because the project good is not sold for USD, this approach requires nding some proxy, a good close to the project good that is priced in USD, and substituting its USD price for P(usd) in the above equation.

Two articles that prominently feature the Quantity Theory are and .

My Bio: I joined the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis in 1984 and retired as Senior Research Officer in 2012. While at the Bank, I actively participated in monetary policy briefing sessions and attended Federal Open Market Committee Meetings. Also, I briefed the Minneapolis Fed Board of Directors on economic conditions and the effects of monetary policy.

I taught economics at Virginia Tech, Tulane, Duke, and the University of Minnesota; and I am now a Visiting Scholar at the Bank of Canada and at the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, and a Visiting Professor at the University of South Carolina.

My research focus primarily has been money and banking theory and history, and the relationship between money growth and inflation. My current research is on the implications of new payment systems (such as e-money and bitcoin) for the future conduct of monetary policy.

My wife and I currently reside near Charleston, SC. You can learn more at my website:

was originally published in on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.