Comunicado de imprensa bitcoin: A plataforma descentralizada de jogos TriForce Tokens garantiu sua meta de capitalização mínima na pré-venda em apenas alguns dias, levantando mais de US$ 1 milhão. A pré-venda está acontecendo de 20 de fevereiro até 6 de março de 2018 e oferece aos participantes uma variedade de descontos à medida que avança. Milton […]

From the buried gold of Treasure Island to the seven missing Fabergé

eggs, lost and stolen treasure has long been the stuff of legend and

romance. In bitcoin, though, there are no princesses, dragons, or

(seafaring) pirates, and not much romance. Fortunes are often lost

simply because private keys are wiped from laptops, the slips of paper

they’re printed on go missing, or they’re stolen by hackers.

Mundane as it may seem, key management is critically important in any

cryptographic system. Cryptocurrencies like bitcoin and Ethereum are no

exception. Lost or stolen keys can be catastrophic, but handling keys

well is notoriously hard. Users need to protect their keys against theft

by wily hackers, without securing them so aggressively that they might

be lost. Key management is especially challenging in business settings,

where often no one person is trusted with complete control of resources.

A common, powerful approach to key management for cryptocurrencies is

multisig transactions, a way to distribute keys across multiple users.

Such key distribution is referred to more generally as secret sharing.

We have just released a

addressing a critical problem

with secret sharing in general and in cryptocurrencies in particular. We

refer to this problem as access-control paralysis.

A few months ago, an acquaintance approached us with a simple but

intriguing problem, a good example of real-world key distribution

challenges.

This person—we’ll call our whale friend Richie—shared ownership of a

large stash of bitcoin with two business partners. Richie and his

partners naturally didn’t want any one partner to be able to make off

with the BTC. They wanted to ensure that the BTC could only be spent if

they all agreed. There’s a simple solution, right? They could use

3-out-of-3 multisig where all three would then need to sign a transaction

involving the BTC. Problem solved! Or is it?

However, that’s not the whole story. Richie and his partners were also

worried, naturally, about what would happen in one of their keys was

lost. The device storing a key might fail, a key might be deleted by

mistake, or, in some very unfortunate cases, such as a car accident, a

shareholder might physically lose the ability to access her key. The

result would be a complete loss of all of their BTC.

This isn’t the only bad scenario. It’s also possible that Richie and his

partners have different ideas about how the money should be spent, and

can’t come to an agreement. Worse still, one malicious or piggish

shareholder might blackmail the others by withholding her key share

until they pay her. In this case, the BTC could be lost, temporarily or

permanently, to indecision or malice.

We use the term paralysis to denote any of these awkward situations

where the BTC can’t be spent. Unfortunately, N-out-of-N multisig doesn’t

solve the paralysis problem. In fact, it makes the problem worse, as

loss of any one key is fatal.

Richie and his business partners.

For this reason, avoiding paralysis while meeting the goal of Richie and

his partners—i.e., requiring full agreement to spend the BTC—seems

impossible. Actually, it is impossible with secret sharing alone,

because of a basic paradox. Suppose we have an N-out-of-N multisig

scheme, which we clearly need to enforce full partner agreement for

transactions. If N-1 shareholders can somehow gain access to the BTC

when one share goes missing, they can simply pretend that one share has

gone missing and access the fund on their own. In other words, what we

had to begin with was really some kind of (N-1)-out-of-N multisig,

which is a contradiction.

Richie’s problem seems to have left us in a state of paralysis…

Thanks to the advent of two powerful technologies, blockchain and

trusted hardware–Intel SGX, in particular—it turns out that we can

actually resolve this paradox. We can do so efficiently and in a very

general setting—to the best of our knowledge, for the first time.

Toward this end, we introduce a novel technique called a Paralysis

Proof System.

As you’ll see, fairly general Paralysis Proof Systems can be realized

relatively easily in Ethereum using a smart contract—no SGX required.

We present an example Ethereum contract in our paper. Scripting

constraints in bitcoin, however, necessitate the use of SGX and also

introduce some technical challenges. Prime among these is the fact that

without significant bloat in its trusted computing base, an SGX

application cannot easily sync securely with the bitcoin blockchain.

Our approach leverages a novel combination of SGX with a blockchain

that avoids the need for an SGX application to have a trustworthy view

of the blockchain.

The intuition is fairly simple. A trusted third party holds all of the

keys in escrow. If one or more parties cannot or will not sign

transactions, leading to the paralysis described above, the others

generate a Paralysis Proof showing that this is the case. Given this

proof, the third party uses the keys it holds to authorize transactions.

If we have a trusted third party, though, we’re clearly not achieving

the security goal set forth by Richie and his friends. One party

controls all the keys!

This is where SGX comes into play. An SGX application can behave

essentially like a trusted third party with predetermined constraints.

For example, it can be programmed so that it is only able to sign

transactions when presented with a valid proof. (In this sense, SGX

applications behave a lot like smart contracts.) Thanks to SGX, we can

ensure that the BTC can only be touched by a subset of parties when

provable paralysis occurs.

Of course, even given this magic that is SGX, we still need to ensure

that Paralysis Proofs can only be generated legitimately. We don’t want

Richie’s partners to be able to “accuse” him, falsely claiming that he’s

dead by, say, mounting an eclipse attack against the host running the

SGX application. Happily, blockchains themselves provide a robust way to

transmit messages and for a party to signal that she is alive. To

implement a Paralysis Proof System for bitcoin, we take advantage of

this fact, along with a few tricks. For the sake of simplicity, we’ll

focus on the problem of inaccessible keys, setting aside other forms of

paralysis for the time being.

A Paralysis Proof is constructed by showing that a party P is not

responding in a timely way and thus appears to be unable to sign

transactions. The system emits a challenge that the “accused” party must

respond to with what we call a life signal. If there’s no life signal

in response to a challenge for some predetermined period of time (say,

24 hours), this absence constitutes the Paralysis Proof.

For bitcoin, a life signal for party P can take the form of a UTXO of

a negligible amount of bitcoin (e.g. 0.00001 BTC), that can be spent

either by P — thereby signaling her liveness — or by pk_SGX—but only

after a delay. Note that sk_SGX is only known to the SGX application.

Let’s take our example of three shareholders again. Let’s say each of

them possesses a key pair (sk_i, pk_i). First they escrow their BTC

fund—let’s suppose it’s 5000 BTC—to UXTO_0 — an output spendable by

either all of them or pk_SGX. Suppose now that P_2 and P_3 decide to

accuse P_1. Upon receiving their request, the SGX application prepares

the following two transactions and sends them to P_2 and P_3:

t_1 that creates a life signal UTXO_1 of 0.00001 BTC spendable by either pk_1 immediately or by pk_SGX after a timeout (e.g. 144 blocks, 24 hours)

t_2 that spends both UTXO_0 and the life signal UTXO_1, to an address spendable by pk_2 and pk_3 (or pk_SGX optionally, if they want to stay in the Paralysis Proof System).

The shareholders that accused P_1 should therefore broadcast t_1 to the

bitcoin network, wait until t_1 is added to the blockchain, then wait

for the next 144 blocks, and then broadcast t_2 to the bitcoin network.

There are two possible outcomes:

In the case of legit accusation where P_1 is indeed incapacitated, P_2 and P_3 will obtain access once t_2 is mined. This ensures the availability of the managed BTC fund.

In the case of malicious accusation, however, the above scheme ensures that P_1 has the opportunity to appeal while these 144 blocks are being generated. To do so P_1 just spends UTXO_1 with the secret key that is known only to her (the script of t_1 does not require the CSV condition for spending with her secret key). Since t_2 takes both UTXO_0 and UTXO_1 as inputs, spending t_1 renders t_2 a invalid transaction.

The security of life signals stems from the use of a relative timeout

(CheckSequenceVerify) in the fresh t_1, and the atomicity of the signed

transaction t_2. To elaborate, t_2 will be valid only if the witness

(known as ScriptSig in bitcoin) of each of its inputs is correct. The

witness that the SGX enclave produced for spending the escrow fund is

immediately valid, but the witness for spending t_1 becomes valid only

after t_1 has been incorporated into a bitcoin block that has been

extended by 144 additional blocks (due to the CSV condition). Thus,

setting the timeout parameter to a large value serves two purposes: (1)

giving P1 enough time to respond, and (2) making sure that it is

infeasible for an attacker to create a secret chain of 144 blocks faster

than the bitcoin miners, and then broadcast this chain (in which t_2 is

valid) to overtake the public blockchain.

Although we use bitcoin as a running example, the power of Paralysis

Proof Systems extends beyond cryptocurrencies and the techniques behind

them support a range of interesting new access-control policies for

problems other than paralysis. Some of these policies are easy to

enforce in smart contract systems like Ethereum, but others aren’t

because they rely on access-controlled management of private keys, which

can’t be maintained on a blockchain.

For example, Paralysis Proof Systems can be applied to credentials for

decryption. You can use Paralysis Proofs to create a deadman’s switch

for the release of a document, allowing it to be decrypted if a person or

group of people disappear. Here are some other examples of

access-control policies other than paralysis that can be realized thanks

to a combination of blockchains (censorship-resistant channels) plus SGX:

Daily spending limits: It is possible to ensure that no more than some pre-agreed-upon amount—say 0.5 BTC—is spent from a common pool within a 24-hour period. (There are some practical limitations discussed in our paper.)

Event-driven access control: Using an oracle, such as our (which is actually the first public-facing SGX-backed production application), it is possible to condition access-control policies on real-world events. For example, daily spending limits might be denominated in USD, rather than BTC, by providing a data feed on exchange rates. One could even in principle use natural language processing to respond to real-world events. For example, a document with compromising information could be decryptable by a journalist should its author be prosecuted by a federal government.

Upgrading threshold requirements: Given agreement by a predetermined set of players, it is possible to add and/or remove players from an access structure, i.e., set of rules about authorized players. E.g., it is possible to convert a k-out-of-N decryption scheme to a (k+1)-out-of-(N+1) scheme. In a regular secret sharing scheme, upgrading isn’t possible, because a group of authorized players can always reconstruct the key they hold. If an SGX application controls a decryption key, however, it can monitor a blockchain to determine if players have voted for an upgrade. Votes are immune to suppression if they’re recorded on chain.

In general, the combination of SGX and blockchains supports a

fundamental revisitation of access-control policies in decentralized

systems and introduces powerful new access-control

capabilities—capabilities that are otherwise impossible to achieve.

To learn more, read our paper at .

Many interesting extensions of the above are discussed in our paper.

Here are a couple.

As mentioned, it is the scripting constraint of bitcoin that

necessitates the use of SGX. In fact,

we also present a (somewhat less efficient) approach without trusted

hardware that makes use of covenants, a proposed bitcoin feature. We

refer readers to our paper for a covenant-based protocol. The bottom

line is, the complexity of the covenants approach is significantly

higher than that of an SGX implementation (in terms of conceptual as

well as on-chain complexity). As there have been recent proposals to

support stateless covenants in Ethereum, the comparative advantages of

our SGX-based design may prove useful in other contexts too.

In the aforementioned example, the fund can be spent by pk_SGX alone,

but it’s important to note that’s not the only option. In fact, one can

tune the knob between security and paralysis-tolerance to the best fit

their needs.

For example, if the three shareholders only desire to tolerate up to one

missing key share, what they can do is to move the funds into 3-out-of-4

address where the 4th player is the SGX enclave. If all of them are

alive, then they can spend without SGX. If one of them of being

incapacitated, the enclave will release its share if the rest two of

players can show a Paralysis Proof. Therefore, even if the secret of SGX

is leaked via a successful side-channel attack, the attacker cannot

spend the fund unless colluded two malicious players.

This is an interesting line of future research we intend to pursue.

| submitted by |

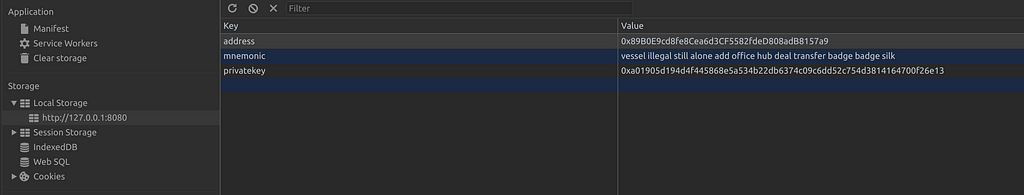

Deploying a decentralized application introduces some interesting security considerations that might not come up in more traditional development.

One important obstacle we’ve run into while working on the Colony dApp is the challenge of keeping locally stored dApp data secure with a distributed storage system like IPFS or Swarm.

In this article I’m going to take a look at the problem from a dApp developer’s perspective, then examine some possible solutions.

The problem of Shared localStorage

IPFS runs a local ‘node’, which comes bundled with a web server. The bundled web server makes it easy for nodes to connect to each other and share data that might be needed somewhere else in the network.

As a decentralized app builder, you’re going to rely on that web server to push and pull your content from node to node, making it instantly available to an end-user as needed.

Assuming that you’re going ‘full decentralized’ and are avoiding anything like DNS or web proxies to keep track of where your content is on the network, the way to access your dApp would ordinarily be to query the local node through a browser using its hash:

Now, let’s say that during normal use your application is going to save data inside your browser’s localStorage — maybe you need to pass some data around, or are keeping a queue of user interactions local to minimize on-chain transactions and save gas costs.

The local storage within your browser is restricted to a specific address context (domain and port). The IPFS node is what gets this context — meaning that any distributed app running through the IPFS web server will be using the same localStorage with read and write access.

This is potentially a big problem.

Some helper dependencies for a dApp by default use localStorage to temporarily keep keys in plaintext.

Another potential leak is packages that save their memory state so that it can be restored at a later time. Flux-like libraries ordinarily are (relatively) safe because they run only in memory — but enabling state persistence will put that memory state into localStorage and thus open it up to potential attackers.

Strategies for mitigation

Unfortunately, there’s no magic bullet for security — as a dApp developer any adaptation made for the sake of security is likely going to require some concessions in other aspects of development.

Here are some compromises you can make:

Store no data

This is certainly the safest approach, but it’s a bit like burning your house down to get rid of the cockroaches. There are a lot of features and essential behaviors inside a dApp that store data locally, and you might not have much of an app left after you remove them.

Furthermore, there are a number of libraries out there that use localStorage by default — you’ll have to manually inspect each of your dependencies and remove any that require it, or else modify the libraries yourself.

Encrypt everything

This is a bit more promising in theory, especially since most dApp developers are already on-board with keeping things encrypted by default.

In practice encrypting all your local storage is a bit more troublesome. To encrypt data, one must have a key — but a user can’t store that key within the dApp because it’ll be put inside localStorage and you’ll be back to square one.

One solution is to use a wallet: your dApp will likely be interacting with a blockchain in some way, requiring the user to unlock their wallet to send and sign transactions. Since the wallet will be needed to interact with the dApp anyway, it would be possible to use each account’s privatekey to encrypt local storage.

This, however, also comes with some drawbacks:

You must ask users for their plaintext private key each time they want to interact with localStorage.Key management software like MetaMask will not work because it never exposes the user’s private key.Use exclusively Swarm and Mist

Mist is built as both a dApp and Ethereum browser, so it offers some special advantages for the problem.

Mist supports Swarm'sbzz protocol by default, so you could set up an ens address to point to your dApp’s hash, and then use Mist to browse your dApp without worry.

Unfortunately, this will only solve the problem for users that access the dApp through Mist.

A user running a local Swarm node will still have to access via localhost, which will still be (potentially) leaking data to other dApps.

Create a browser extension for your dApp

Running your app through a browser extension will result in it getting a separate context (it won’t be on localhost:8080 anymore) — but it kind of defeats the purpose of decentralizing an app only to rely on a central authority like chrome web store for management and distribution.

Also, now you’ll have to create and maintain a separate extension for each browser that you want to support, and update each through its own specific centralized app store. Yuck.

Create a standalone desktop app

As before, creating a standalone app is a way to separate your dApp into its own context, meaning it’d get its own wrapper (in this case, electron).

A standalone desktop app has the added benefit of being able to bundle external libraries and anything else you might need, including a separate instance of IPFS itself.

Also as before, there are some concessions:

Unless you want to distribute the app exclusively on bittorrent, you’ll need to find a centralized hosted solution for distribution and maintenance.You’ll have to maintain a separate repository just for the electron desktop app.If you want to use IPFS for any other service, you’ll likely end up running multiple nodes on the same machine, which could get messy.Proxy your app to a domain name

By using another web server to proxy your local node, there are two advantages:

First, now your dApp has a nice friendly human-readable address, instead of a long cumbersome hash. Second, your app would then have its own context, and wouldn’t share localStorage.

Proxying does, however, cross the line of ‘true’ decentralization — users will again have to rely on a centralized server to access a decentralized service. Boo.

It’s still early days for decentralized app developers. Problems like this are ubiquitous throughout the emerging ‘decentralized protocol stack’ — and it’ll likely be a while before we come up with more elegant solutions.

In the future, support for a native IPFS or Swarm node within a browser would solve this problem— and eliminate the need to bundle a web server with decentralized file storage at all. Users could input something like ipfs://QmcefGgoVLMEPyVKZU48XB91T3zmtpLowbMK6TBM1q4Dw/ and get access to a dApp directly, with each unique hash being assigned its own context.

The Mist and IPFS teams are aware of the issue, and hopefully will be incorporating a solution into future releases.

For now, though, it’s helpful to find what workarounds we can and to share them with the rest of the community.

If you’re a developer working on your own decentralized app, hopefully this article has been helpful to you in structuring your code to avoid data leakage — if you’ve devised another solution that wasn’t mentioned above, share it!

Thanks to Alex Rea and Griffin Hotchkiss for their help in drafting this article.

is a Javascript developer who spends most of his time in a terminal emulator.

For the past decade he’s been working in the tech industry doing sysadmin work, back-end development and even some electronics.

When not writing code at he pursues his passion for flying.

Colony is a platform for open organisations.

Follow us on sign up for (occasional) , or if you’re feeling old skool, drop us an email.

was originally published in on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.