In this review article, I have covered a broad range of topics-Classical cryptography, Quantum computers, Quantum cryptography and the impact to bitcoin security in the near term and long term due to the advent of quantum computers. This is an extremely interdisciplinary field touching upon mathematics, computer science, physics, quantum information theory and nanotechnology. Each of these areas has an entire field of research associated with it. Thus, every effort has been made to provide references to more detailed works to help the reader to probe deeper.

Cryptography today

Cryptography is the technique by which a message that needs to be transmitted over an insecure channel is rendered indecipherable to any unauthorized party who might eavesdrop. To achieve secure transmission, an algorithm is used to combine the message with additional information to produce a cryptogram. The algorithm is also called a cryptosystem or cipher and the additional information is known as the key. The technique is known as encryption [1]. Encryption in conventional cryptography is based on mathematical relations wherein security is ensured by choosing mathematical functions that have superpolynomial time complexity [1].

Current classical cryptography methods used in all our financial transactions and other encrypted messages draw their strength from mathematics. For example, take two prime numbers 23 and 37 and upon multiplication you get 851. We have an algorithm to multiply these numbers but unfortunately do not have an algorithm to identify their constituent primes if we start with 851. The only way to do this is brute force method where we try various combinations of prime numbers until we arrive at the two constituent prime numbers. This type of ‘one way computation’ is the basis of most of the secure communications that we have today. This is how the public and private keys are combined using a hard mathematical relationship. Prime numbers play a key role in cryptography. Two problems are used in creating secure communications-factoring and the discrete logarithm problem [2].

As the numbers get larger the amount of time taken by classical computers to obtain the constituent primes increases exponentially. For a 256-bit long number, it takes nearly as long as the age of the universe to decode the primes. Thus, in theory classical cryptography can be broken but in practice its next to impossible. For a review of the three most frequently used Classical Cryptography schemes employed worldwide, please read my review article titled Quantum Cryptography-State of Art and Future Perspectives [1].

The above ‘hard problem’ can become extremely simple (again in theory) for a quantum computer as there are dedicated quantum algorithms to factorise large numbers using a Quantum Computer. A 256 bit number will only take few minutes to factorise thus breaking any of the worlds’ codes. The dependency here is on building a working quantum computer that can perform the above algorithms efficiently.

Quantum Cryptography: answer to Quantum computers to safeguard communications

Quantum cryptographic systems rely on Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle. A quantum system when measured is disturbed and yields incomplete information about the state it was in prior to the measurement. Eavesdropping on a quantum communication channel therefore alerts legitimate users.

Quantum key distribution (QKD) [3] is a method in which quantum states are used for encryption. The first Quantum Key Distribution used in Quantum Cryptography scheme was presented by Bennett and Brassard in 1984 and is now commonly referred as BB84 protocol [4]. The first experimental demonstration of the protocol was performed in 1991 using the polarization states of single photons to transmit a random key. QKD allows two parties to share a unique key securely and then leverage the ‘one time pad’ system to ensure that they are able to communicate with absolute secrecy.

The No Cloning Theorem [5] states that an unknown quantum state cannot be cloned. If such a quantum copier existed, then ‘Eavesdropper’ could have measured the quantum system, and then could have sent the copied state to ‘Receiver’. Since cloning is not possible, an act of eavesdropping would be detected. The possibility of detection of eavesdropping makes quantum cryptography superior to conventional cryptography.

The fact that quantum cryptography draws largely from the fundamental randomness of quantum mechanics yields a robust cryptographic system. Two parties initially sharing no secret information can thus exchange a secret random cryptographic key using quantum cryptography that is secure against an eavesdropper. The strength of quantum cryptography is that the codes that are generated are not even in theory decodable. For a more thorough review of the field of quantum cryptography beyond QKD please read this review [6].

Role of Cryptography in bitcoin protocol

bitcoin uses elliptic curve public-key cryptography (ECDSA) as current signature scheme. ECDSA is an implementation of the Digital Signature Standard (DSS) based on Elliptic Curve Cryptography [7]. Like integer factorization [2], ECDSA has no known reasonably fast (e.g. polynomial-time) solution on a classical computer [8].

Peter Shor’s polynomial time (limited time) quantum algorithm is extremely efficient in integer factoring applications compared to classical algorithms [9] and can break ECDSA thereby endangering bitcoin communications. A Quantum capable adversary could potentially steal bitcoins from the public key information and indulge in double spending on the bitcoin network. [10]

Most blockchain platforms rely on the ECDSA or the large integer factorization problem (RSA) to generate a digital signature [11]. The security of these algorithms is based on the assumption of computational complexity of certain mathematical problems as previously described [12].

Another threat to bitcoin protocol is Grover’s algorithm, which can dramatically speed up function inversion. This allows the generation of a modified pre-image from a given hash (a hash collision) allowing a signed data block to be modified [13]. Grover’s algorithm running on a Quantum Computer allows the attacker to mine faster and meddle with the transactions of the Blockchain. It has the potential to create a 51% attack scenario (majority of the nodes collude to alter the blockchain). However, the specialized ASIC miners are extremely fast compared to the estimated clock speed of near-term quantum computers and thus its not expected to pose a serious threat in the short term [14].

Quantum Computers and their impact on cryptography

With quantum computing, we are witnessing an exciting and very promising merging of three of the deepest and most successful scientific and technological developments of modern era: quantum physics, computer science, and nanotechnology. Quantum computers have the potential to perform certain calculations billions of times faster than any silicon-based computer. A functional quantum computer will be invaluable in factoring large numbers, and therefore extremely useful for decoding and encoding secret information [1]

Classical computers work using bits-0s and 1s- whereas quantum computers work using qubits (quantum bits). A classical bit can only exist as a 1 or 0 at any given time. But a qubit exists as a combination of a 0 AND 1- both at the same time. When measured, the quantum state gets disturbed and the qubit collapses into a 0 or 1. But until measurement it has multiple possibilities. When this superposition of qubits is combined with quantum entanglement, a new paradigm of computing is possible. Entanglement means that qubits in a superposition can be correlated with each other; that is, the state of one (whether it is a 1 or a 0) can depend on the state of another.

There have been several recent developments in building practical Quantum Computers through a race between IBM, Microsoft, Google and other technology companies [15,16,17,18]. For a detailed technical overview of the field of Quantum Computing and Quantum Information please read a seminal work that is one of the most cited books in this area of physics [19].

We understand the physics behind building a quantum computer but the real challenge is one of engineering. Qubits suffer from decoherence meaning that the information stored in the qubits is lost due to the interaction with the environment and to scale the control infrastructure of large numbers of qubits in the range of millions is no trivial challenge [20].

How to safe guard bitcoin in the world of a Quantum computer capable attacker?

According to this paper [14], a quantum computer running Shor’s algorithm can break elliptic curve signatures in ten minutes (approximately bitcoin block formation time) as early as 2027.

Post-quantum cryptography is a new branch of cryptography interested in a suite of algorithms which are believed to be secure even against attackers equipped with quantum computers [21]. This is not to be confused with Quantum Key Distribution or Quantum Cryptography which uses principles of quantum mechanics to safeguard communications. With Post-quantum cryptography we are very much in the realm of mathematical functions although much more complex cryptographic hash function based rather than prime factorization.

There are many important classes of cryptographic systems beyond RSA, DSA and ECDSA:

• Hash-based cryptography. The classic example is Merkle’s hash-tree public-key signature system (1979), building upon a one-message-signature idea of Lamport and Diffie

• Code-based cryptography. The classic example is McEliece’s hidden-Goppa-code public-key encryption system (1978)

• Lattice-based cryptography. The example that has perhaps attracted the most interest, not the first example historically, is the Hoffstein–Pipher–Silverman “NTRU” public-key-encryption system (1998)

• Multivariate-quadratic-equations cryptography. One interesting example is Patarin’s “HFEv−” public-key-signature system (1996), generalizing a proposal by Matsumoto and Imai

• Secret-key cryptography. The leading example is the Daemen–Rijmen “Rijndael” cipher (1998), subsequently renamed “AES,” the Advanced Encryption Standard

These systems are believed to resist classical computers and quantum computers. Nobody has figured out a way to apply “Shor’s algorithm” to any of these systems. Grover’s algorithm does have some applications to these systems; but Grover’s algorithm is not as fast as Shor’s algorithm, and cryptographers can easily compensate for it by choosing somewhat larger key sizes.

In a post-quantum computer world, in the near term we can expect to see a secure transition from bitcoin’s current signature scheme to a quantum-resistant signature scheme [14]. It is important to note that Post-quantum cryptography is rapidly expanding but still has a great deal of uncertainty and no developed standards yet [13].

However, in the long term things may need a bigger paradigm shift.

QKD can be leveraged to exchange keys prior to transmission messages. This can then be used in conjunction with existing classical Blockchain protocol to protect against a Quantum computer equipped attacker.

We may see the development of a ‘Quantum bitcoin’ that is built leveraging the principles of Quantum Mechanics using quantum states as bits moving away from classical bits. Such a “Quantum bitcoin,” may use a classical blockchain ledger but uses quantum methods to mine and verify a block. There are also protocols to encode and store information such as a ledger in a quantum system making the information tamper-proof. There are also quantum bit commitment protocols which may be seen as a type of alternative to digital signature schemes. Many of these ideas show promise, however all of these technologies are currently at very low technology readiness levels with many of the technologies being at least as difficult to implement as quantum computing itself [13]. In addition, we may even see purely ‘Quantum bitcoin’ protocols that actually run on Quantum Computers leveraging the no-cloning theorem [22].

Conclusion

In summary, there is no immediate threat to current classical cryptographic protocols because of quantum computers as the number of qubits required is still at least two orders of magnitude larger than those capable currently. In the near term, cryptographic protocols can adjust to growing computing power by adopting larger keys. In the medium term a shift from classical resistant schemes to quantum resistant cryptographic schemes is expected. However, in the long term, we can expect to see a shift to Quantum Cryptography and a Quantum bitcoin that leverages the principles of quantum mechanics to design new systems of Cryptography and bitcoin from the ground up.

References

1. V. Teja et al. “Quantum Cryptography: State-of-Art, Challenges and Future Perspectives”, Proceedings of the 7th IEEE International Conference on Nanotechnology, August 2–5, 2007, Hong Kong

2. R. E. Crandall and C. Pomerance. Prime numbers: A computational perspective, Chapter 5. Springer, 2005

3. C. Elliott, D. Pearson and G. Troxel, “Quantum Cryptography in Practice”, Preprint of SIGCOMM 2003 paper.

4. P. W. Shor and J. Preskill, “Simple Proof of Security of the BB84 Quantum Key Distribution Protocol”, Phys. Rev.Lett. 85, 2000, pp. 441- 444.

5. N. Gisin, G. Ribordy, W. Tittel and H. Zbinden, “Quantum Cryptography” ,Reviews of Modern Physics, vol. 74, January 2002, pp. 145–195

6. Anne B and Christian S. Quantum Cryptography Beyond Key Distribution. Dec 2015. Accessed: 2018–04–01

7. X9-Financial Services Public Key Cryptography For The Financial Services Industry: The Elliptic Curve Digital Signature Algorithm (ECDSA) c . 1998

8. A. Menezes. Evaluation of Security Level of Cryptography: The Elliptic Curve Discrete Logarithm Problem (ECDLP). 2001

9. P. W. Shor. Polynomial-Time Algorithms for Prime Factorization and Discrete Logarithms on a Quantum Computer. AT&T Research, 1994

10. I Stewart et al. Committing to Quantum Resistance: A Slow Defence for bitcoin against a Fast Quantum Computing Attack, Accessed: 2018–04–01

11. Witte, J.H. The blockchain: A gentle four page introduction. arXiv:1612.06244. Accessed: 2018–04–01

12. E.O. Kiktenko, N.O. Pozhar, M.N. Anufriev, A.S. Trushechkin, R.R. Yunusov, Y.V. Kurochkin, A.I. Lvovsky, and A.K. Fedorov. ‘Quantum-secured blockchain’. Technical Report arXiv:1705.09258, Cornell University Library, May 2017 [online]. Accessed: 2018–04–01

13. Brandon Rodenburg, Stephen p. Pappas. Blockchain and Quantum Computing. MITRE Corporation project 25SPI050–12, 2017 Accessed: 2018–04–01

14. Divesh Aggarwal, Gavin K. Brennen, Troy Lee, Miklos Santha, and Marco Tomamichel. Quantum attacks on bitcoin, and how to protect against them. Technical Report arXiv:1710.10377, Cornell University Library, Oct 2017

15. Abigail B and Matt R. What are quantum computers and how do they work? WIRED explains. 16th Feb 2018. . Accessed: 2018–04–01

16. Masoud Mohseni et al. Commercialize quantum technologies in five years. 3rd March 2017. Accessed: 2018–04–01

17. Rory C Jones. Microsoft gambles on a quantum leap in computing. BBC News. 31st March. 2018. Accessed: 2018–04–01

18. Will Knight. ‘Intelligent Machines-Serious quantum computers are finally here. What are we going to do with them?’ 21st Feb, 2018. Accessed: 2018–04–01

19. M. A. Nielsen and I. Chuang. Quantum computation and quantum information, 2002. ISBN: 978–1–107–00217–3

20. C. G. Almudevar et al. The engineering challenges in quantum computing. IEEE. 2017 Design, Automation & Test in Europe Conference & Exhibition (DATE).

21. Daniel J. Bernstein. Introduction to post-quantum cryptography. org/www.springer.com/cda/content/document/cda_downloaddocument/ 9783540887010-c1.pdf. Accessed: 2018–04–01

22. Jonathan Jogenfors. Quantum bitcoin: An Anonymous and Distributed Currency Secured by the No-Cloning Theorem of Quantum Mechanics. April. 2016. Accessed: 2018–04–01

Discount is 29% and min. contribution is just 0.01 ETH!

1 ETH = 11 200 UBC

It will last till April, 21.

INVEST NOW on !

CCCH token is tied to the hiring of employees in the company. The company will have to spend CCCH tokens to find and hire an employee. The number of tokens is limited.

Companies will receive an application for hiring and communicating with candidates. HR managers will be able to create a vacancy, using the opportunities of smart contracts, and to check core information about the candidate in the blockchain: what are his/her verified skills, competencies, completed projects, etc. Blockchain will provide more reliable information about applicants, which is now lacking in companies.

We want to create the world where people are rewarded for their skills and achievements at work. And companies receive a reliable rating of specialists to facilitate the candidates’ selection process.

Decentralization provides the best opportunities for creating the brand new ecosystem. Each person will be able to show professionalism and develop a reputation of a reliable employee for a couple of clicks.

and or Email contact@ccch.space

UniDAG Backup Framework

The UniDAG backup framework is a set of software and libraries for creating a structured, hard-to-change linear database, based on the dagchain and cryptographic hashing algorithms.

Architecture

The UniDAG backup framework is designed for use on individual devices.

Scheme of work

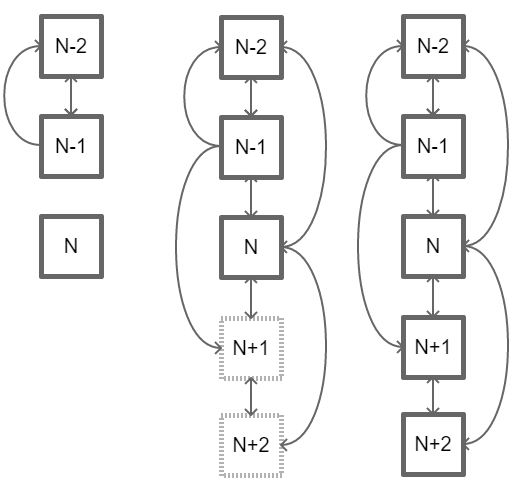

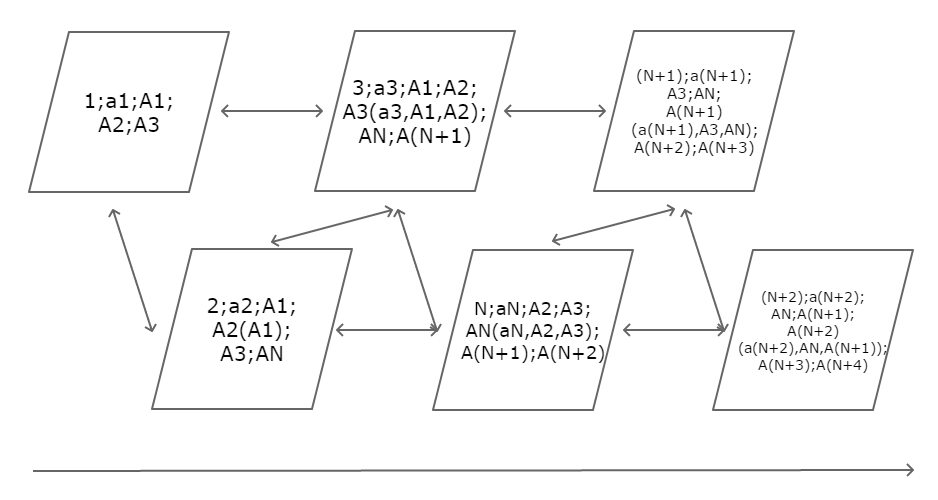

When constructing the dagchain, two directed ribs (interconnections between blocks) are used in one direction and 2 directed ribs in the opposite direction. At an arbitrarily taken time, the last block actually has only 2 edges and 2 “reserved places”. Each block closes the 2 previous blocks and is closed by 2 subsequent ones.

Stages of work:

Formation of block with serial number N.Adding an “open” block N to the dagchain. “Closing” the block N previous blocks with serial numbers (N-1) and (N-2) respectively.Formation of the block with the serial number (N + 1).Adding an “open” block (N + 1) to the dagchain. “Closing” the block (N + 1) of previous blocks with serial numbers N and (N-1) respectively.Formation of the block with the serial number (N + 2).Adding an “open” block (N + 2) to the dagchain. “Closing” block N previous blocks with serial numbers (N + 1) and N, respectively.

When the block is generated, the data is hashed. Then the hashes of the two previous blocks are taken with the received data hash, and they are hashed together to obtain the hash of its own block. Exception: the first two “genesis” blocks. All hash sums are written to the block header. At the same time, two places in the block header are reserved for the 2 hashes of subsequent blocks, and thus the block is opened. When the 2 subsequent blocks are added to the dagchain, they are written to the header of the first block of the hash of their blocks and thus “close” the first block.

For more information,please visit