bitcoin is more than just a digital currency; it is a payment system built on a public, distributed ledger known as the blockchain.In this system, transactions are not recorded one by one in isolation. Instead, thousands of individual transfers of bitcoin are collected, verified, and grouped together into structures called “blocks.” These blocks are then cryptographically linked to one another,forming the blockchain that every node in the peer‑to‑peer network independently maintains and validates.

Understanding how transactions are bundled into blocks is essential to understanding how bitcoin works at all. The process determines which payments are confirmed, in what order they are recorded, and how the network prevents double‑spending without relying on a central authority. It is also at the core of bitcoin’s security model and its incentive structure for miners, who compete to assemble candidate blocks and add them to the chain.

This article explains, step by step, how individual bitcoin transactions move from the network “mempool” into a mined block, how miners choose which transactions to include, and how the final block becomes an immutable part of the blockchain ledger.

Understanding the Lifecycle of a bitcoin Transaction From Broadcast to Inclusion in a Block

Once a wallet signs a payment with the sender’s private key, it is indeed broadcast to the peer‑to‑peer network of bitcoin nodes, which collectively maintain the distributed ledger known as the blockchain . Neighboring nodes validate the basic rules before relaying the transaction further: is the signature valid, are the inputs unspent, and does the transaction respect protocol limits? During this propagation phase, the transaction begins in a mempool (memory pool) on each node, a kind of waiting room for unconfirmed payments. At this stage, the transfer is visible on network explorers, but it is not yet part of bitcoin’s canonical history and can, in rare cases, still be replaced or dropped if fees are too low.

Miners continuously scan their local mempools to assemble candidate blocks, prioritizing transactions that pay higher fees per byte because fees are their primary compensation in addition to the block subsidy . A simplified view of what happens during selection includes:

- Fee-based sorting – higher fee density transactions are preferred.

- Rule enforcement – only valid, non-conflicting transactions are chosen.

- Size constraints – the total data must fit within the block size/weight limit.

These chosen transactions, plus a special coinbase transaction that creates new BTC, form the block’s content, which miners then hash repeatedly in a proof-of-work race. The first miner to find a valid hash announces the block to the network, proposing an updated state of the ledger for everyone to adopt .

When other nodes receive this newly mined block, they independently verify every rule: proof-of-work difficulty, block size, and the validity of each included transaction. If everything checks out, the block is appended to their local copy of the blockchain, and the transactions inside gain their first confirmation. Over time, as more blocks are built on top of this one, the number of confirmations increases, making the transaction increasingly resistant to reversal . From the user’s perspective, the lifecycle looks like a progression from “pending” in the mempool to “securely settled” on-chain, with the economic value of the payment-often tracked against a live BTC/USD price feed -gradually becoming part of bitcoin’s immutable transaction history.

How Nodes Validate Transactions Ensuring Authenticity and Preventing Double Spending

Every full node on the bitcoin network independently checks each new transaction before it’s allowed anywhere near a block. The node parses the transaction, verifies the cryptographic signatures with the sender’s public key, and ensures that the referenced unspent transaction outputs (UTXOs) actually exist and haven’t been used before. This is absolutely possible as bitcoin operates on a transparent, append-only ledger where all prior blocks of transactions form a shared public history, chained together to prevent tampering and provide a permanent record of each spend. If any rule is violated-even slightly-the node simply rejects the transaction and refuses to relay it to peers.

To avoid double spending, nodes maintain a live view of the UTXO set and apply strict consensus rules whenever a transaction arrives. When two conflicting transactions attempt to spend the same output, nodes evaluate them according to protocol rules and network propagation, ultimately accepting only the version that becomes part of the longest valid chain. This process relies on proof-of-work mining, where blocks of verified transactions are chained together using cryptographic hashes, making it computationally infeasible to rewrite history without redoing an enormous amount of work. Through this combination of local validation and global chain consensus, the network ensures that each bitcoin can be spent only once.

From the perspective of a node operator,validation is a checklist-driven process enforced identically by thousands of machines worldwide. Core checks include:

- Structural integrity – Is the transaction correctly formatted and within size limits?

- Signature validity – Do digital signatures correctly authorize spending of the referenced outputs?

- Script rules – Does the locking/unlocking script pair evaluate to true under consensus rules?

- UTXO availability – Are the inputs unspent and confirmed in the existing chain state?

- Economic sanity – Are outputs ≤ inputs, with the difference correctly accounted as a fee?

| Check type | Purpose |

|---|---|

| Signature check | Confirms the spender’s identity |

| UTXO lookup | Prevents reusing spent outputs |

| Chain consistency | Keeps history immutable and ordered |

The Role of the Mempool Why Transactions Wait and how They Are Prioritized

Before a payment ever reaches a block, it usually spends some time in a kind of digital waiting room known as the mempool (memory pool). Each full node in the bitcoin network keeps its own version of this temporary database, storing valid but unconfirmed transactions it has seen on the peer‑to‑peer network . When network activity is light, transactions can move through this pool quickly; when traffic spikes, the mempool can become congested, and users effectively compete for limited block space. This is why two transactions broadcast at nearly the same time can experience very different confirmation times, depending on network load and fee levels.

Miners treat the mempool like a marketplace of pending transactions, selecting which ones to include in the next block they attempt to mine. As each block is limited in size and weight, miners usually fill it with the most economically attractive transactions first, aiming to maximize fee revenue on top of the fixed block subsidy paid in newly created bitcoin . In practise, this means transactions are frequently enough sorted by fee rate (fee per byte or per virtual byte) rather than just the absolute fee amount. As a result, a smaller transaction with a high fee rate may be chosen ahead of a very large transaction that pays a higher total fee but offers less value per unit of block space.

For users, understanding how this queue operates helps explain why increasing the fee can speed confirmation. Nodes may apply minimum relay fee policies, dropping extremely low‑fee transactions from their mempools, while miners usually prioritize entries that offer the best reward for limited capacity . In practice, wallet software often estimates the current mempool state and suggests a fee level based on desired confirmation speed. Typical factors shaping a transaction’s place in line include:

- Fee rate: Higher fee per vbyte generally moves a transaction closer to the “front” of the mempool.

- Transaction size: Larger transactions consume more block space and must pay more to achieve a competitive fee rate.

- Network congestion: When demand for block space is high, mempools swell and only the highest fee rates clear quickly.

- policy rules: Nodes and miners may impose custom minimums or filters, affecting which transactions stay visible.

| Condition | typical Fee Rate | Likely Confirmation |

|---|---|---|

| low congestion | low-medium | Next few blocks |

| Moderate congestion | Medium | Within 3-6 blocks |

| High congestion | High | Next block or two |

Transaction Fees and Incentives How Miners Choose Which Transactions to include

Every node on the bitcoin network receives a flood of pending payments, but miners are economically motivated to be selective because each block has a strict size limit of roughly 1-4 MB, depending on how transactions are structured . rather than simply picking transactions at random, miners calculate which ones will maximize their revenue from transaction fees, on top of the fixed block subsidy that currently rewards miners with newly created BTC . In practice,they evaluate the fee per virtual byte (sat/vByte),a measure of how much fee is paid relative to the transaction’s data footprint,and prioritize those that pay more per unit of space.

Within the local mempool (the pool of unconfirmed transactions each node maintains), miners or mining pools typically run algorithms to assemble a block template that packs in as much fee revenue as possible. Common priority signals include:

- Fee density (sat/vByte): High fee-per-byte transactions rise to the top of the selection list.

- Ancestor and descendant sets: If a low-fee transaction is the parent of a high-fee child (fee bumping), miners may include both to unlock the combined fees.

- Policy rules: Some pools filter out transactions that violate network norms, even if they pay high fees.

This mechanism creates a marketplace where users effectively bid for faster inclusion by attaching more competitive fees when the network is congested.

| Transaction Type | Typical Fee Priority | Miner Incentive |

|---|---|---|

| High sat/vByte payment | Included early | Maximizes fee income |

| Low-fee, large size | Deferred or dropped | Poor use of limited block space |

| CPFP/fee-bumped set | Often prioritized | Combined fees justify extra bytes |

| Standard, medium fee | Included when space allows | Fills remaining block capacity |

Over time, as the fixed block subsidy halves roughly every four years, the role of fees as the main long-term security incentive is expected to increase . This design aligns miner behavior with network health: miners are paid directly by users who value quick confirmation, while users who are less time-sensitive can opt for lower fees and wait for less congested blocks.

Constructing a Candidate Block From Selected Transactions to Block Header Creation

Once a miner has curated a set of valid, high-fee transactions from the mempool, they assemble them into a provisional data structure often called a candidate block. This bundle starts with a special transaction,the coinbase transaction,which creates new BTC according to the protocol’s issuance schedule and collects all transaction fees in the block as a reward for the eventual winner of the proof-of-work race . Behind the scenes,the miner must respect strict constraints,such as the maximum block weight limit and standardness rules,to maximize revenue without producing an invalid block. The remaining transactions are then ordered and structured so they can be efficiently hashed and verified by every node in the network .

From this ordered list of transactions, the miner constructs a merkle tree, a hierarchical hashing structure where each leaf is the hash of a transaction and each parent node is the hash of its two children. Repeatedly hashing pairs of nodes eventually produces a single root hash known as the merkle root, which uniquely commits the block to every included transaction without storing them individually in the header. This design allows nodes to verify that a specific transaction is included in a block using compact proofs rather than downloading all data,a crucial optimization for lightweight clients and large-scale network participation . At this point, the candidate block is fully defined at the transaction level and ready to be summarized into its compact header.

The block header acts as a cryptographic summary and work target for miners.It is indeed a fixed-size structure containing key fields that together define the block’s identity and difficulty target:

- Version – signals which consensus rules the block follows.

- Previous block hash – links the block to its parent, forming the blockchain.

- Merkle root – commits to all transactions chosen for the candidate block.

- Timestamp – miner’s claim of when the block was created.

- nBits (target) – compact depiction of the current difficulty.

- Nonce – a 32-bit field miners iterate while searching for a valid hash.

| Header Field | Purpose |

|---|---|

| Previous Hash | Chains blocks together |

| Merkle Root | commits to transactions |

| nBits | encodes difficulty target |

| Nonce | Search space for proof-of-work |

Proof of Work in Practice How Mining Secures the Block Bundling Process

In bitcoin,miners act as competitive auditors who verify pending transactions and package them into candidate blocks. each block includes a list of validated transactions, a reference (hash) to the previous block, a timestamp, and a special variable called a nonce. To make this block acceptable to the network, miners must find a nonce that produces a block hash below a dynamically adjusted target. This computational challenge is the essence of Proof of Work (PoW): it requires costly computation to create a valid block, but makes verifying that block trivial for every other node.

This mechanism directly protects the block bundling process from manipulation. Because miners must expend real-world resources to solve the PoW puzzle, it becomes economically irrational for an attacker to rewrite history unless they control a majority of the network’s hashing power. As an inevitable result, once transactions have been included in multiple confirmed blocks, reversing them becomes increasingly infeasible. The security of this process rests on a few practical pillars:

- Costly computation: Mining consumes electricity and specialized hardware resources.

- Easy verification: Nodes can verify a block’s hash and PoW in milliseconds.

- Chain selection rule: honest nodes follow the chain with the most cumulative work.

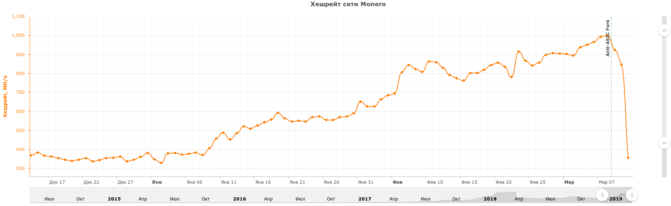

- Difficulty adjustment: The network regularly recalibrates mining difficulty to target ~10-minute blocks.

| Element | Role in Securing Bundled Blocks |

|---|---|

| Nonce | Randomizes block hashes,enabling the PoW search process. |

| Difficulty Target | Controls how hard it is indeed to find a valid block hash. |

| Hash Rate | Represents total computational power defending the chain. |

| Cumulative Work | Determines which chain is considered the canonical history. |

Block Propagation Across the Network Minimizing Orphans and Ensuring Consensus

Once a miner discovers a valid block, it is indeed promptly broadcast to neighboring nodes, which then verify its proof-of-work, transaction signatures, and adherence to consensus rules before relaying it further across the network.This rapid, hop-by-hop dissemination is essential because bitcoin is a decentralized, peer-to-peer system, with no central server coordinating updates. To streamline this process and reduce bandwidth usage, nodes often exchange compact block data rather than full block contents first, then request only the missing pieces they need. As a result, the majority of honest nodes converge on the same latest block within seconds, supporting a consistent, globally shared ledger.

Delays in this propagation can lead to orphaned (stale) blocks, which occur when two miners find valid blocks nearly together, and different parts of the network briefly extend different versions of the chain.Eventually, one branch becomes longer as more proof-of-work is added, and the network automatically treats it as the valid chain, while the competing block is discarded. Common contributors to orphan rates include:

- High network latency between geographically distant nodes

- Limited bandwidth or overloaded peers struggling to relay data quickly

- Large block sizes that take longer to transmit and validate

| Factor | Effect on Orphans |

|---|---|

| Faster propagation | Fewer competing blocks |

| lower latency | Quicker chain convergence |

| Efficient block encoding | Reduced stale block rate |

To keep orphan rates low and maintain consensus, bitcoin relies on a mix of protocol rules and network-level optimizations. Nodes follow the rule of extending the chain with the most cumulative proof-of-work, which mathematically aligns incentives so that honest miners naturally converge on a single history of transactions. Simultaneously occurring, techniques such as compact blocks, peer diversity (connecting to nodes in different regions), and improved routing policies help blocks spread quickly, even as the transaction load and market value of bitcoin grow. Together, these design choices ensure that once transactions are bundled into a confirmed block, they are efficiently shared, agreed upon by the majority, and deeply anchored into the blockchain’s immutable history.

Best Practices for Users Optimizing fees and Confirmation Times for Reliable Settlement

To achieve dependable settlement when yoru transaction competes for limited block space,it’s essential to understand how miners prioritize the bitcoin mempool. As miners generally select transactions based on feerate (sats per vbyte) rather than total fee,users should focus on making transactions compact and efficiently structured. Techniques such as consolidating many small UTXOs during off‑peak periods, avoiding unneeded inputs, and using change outputs wisely can significantly reduce the size-and therefore the required fee-of each payment, while still targeting timely inclusion in a block. Monitoring real‑time fee estimates from reputable data sources before broadcasting a transaction helps align your chosen fee level with current network conditions, improving the chances of being mined in the next few blocks.

Different use cases call for different trade‑offs between speed and cost, so fee selection should always be context‑driven rather than one‑size‑fits‑all. For urgent, high‑value transfers, users may deliberately overpay relative to the mempool minimum to obtain faster confirmation and higher settlement assurance, while non‑urgent transactions can safely target lower feerates and tolerate longer waiting times. It is also prudent to leverage wallet features that support replace‑by‑fee (RBF) and Child‑Pays‑for‑Parent (CPFP), which offer a safety net if your original fee proves too low once mempool congestion changes.

Modern wallets increasingly expose tools that let users fine‑tune this balance while still benefiting from the strong security guarantees of bitcoin’s decentralized network . When configuring transactions, users can rely on dynamic fee estimation, saved presets, and clear confirmation‑time targets to standardize their approach. Useful wallet practices include:

- Use dynamic fee estimation: Prefer wallets that automatically suggest feerates based on current mempool data and typical block intervals.

- Enable RBF by default: Opt in so you can increase the fee later without changing the payment details.

- Plan periodic UTXO consolidation: Reduce input clutter during low‑fee windows to keep future payments lean and cheaper.

- Match fee to risk tolerance: For everyday, low‑value payments, choose slower confirmation targets; for irreversible settlement needs, pay for higher priority.

Implications for Scalability and Future Upgrades How Protocol Changes Affect Transaction Bundling

As bitcoin evolves from an experimental digital cash system into a global value network, protocol changes directly shape how many transactions can fit into each block and how efficiently they are processed. The introduction of upgrades such as Segregated Witness (SegWit) and Taproot has altered the structure and size calculation of transactions, effectively increasing the number of transactions that can be bundled without raising the base block size limit, while also improving security and flexibility for more complex spending conditions. These changes do not just tweak technical parameters; they redefine how fee markets behave,how miners prioritize transactions,and how users design their on-chain footprint.

scalability upgrades influence the economics of bundling by reshaping what “optimal” blocks look like under different network conditions.As an example, smaller and more compact transaction formats encourage miners to include a higher volume of low-fee transactions alongside high-fee ones, smoothing out fee volatility and reducing the pressure on users during peak demand. At the same time, protocol improvements enable more sophisticated forms of off-chain or layered transaction aggregation, such as payment channels or batched withdrawals, which reduce the number of individual on-chain records required for a similar economic throughput.In practice, bundling decisions start to depend less on raw byte size and more on a composite of weight units, signature complexity, and strategic fee bidding.

future upgrades are likely to further refine how transaction data is structured, verified, and compressed, with direct consequences for block composition and network capacity.Developers and stakeholders evaluate potential soft forks not only for security and consensus safety, but also for how they change the “shape” of a typical block and the incentives surrounding it. Key areas of focus include:

- More efficient scripting and signatures to reduce per-transaction overhead.

- Enhanced privacy features that still allow compact verification and aggregation.

- Better support for batching and channel closing, lowering on-chain congestion.

| upgrade Focus | Effect on Bundling |

|---|---|

| compact transactions | More entries per block at similar fees |

| Privacy-enhancing scripts | Uniform-looking, easier-to-aggregate spends |

| Layer-2 integration | Fewer on-chain transactions for the same activity |

Q&A

Q: What is bitcoin and how does it work at a high level?

A: bitcoin is a decentralized digital currency that uses a peer‑to‑peer (P2P) network instead of a central authority or bank. Transactions are broadcast across the network, verified by nodes, and recorded in a public ledger called the blockchain. The protocol and software are open source and no single entity owns or controls bitcoin, allowing anyone to participate in the network and its consensus process .

Q: What is a bitcoin transaction?

A: A bitcoin transaction is a data structure that transfers bitcoin value from one set of addresses to another. It typically has:

- Inputs: references to previous unspent transaction outputs (UTXOs) being spent.

- outputs: new UTXOs, each locking a specific amount of bitcoin to a recipient’s address (usually via a script).

Once created and signed with the sender’s private key, a transaction is broadcast to the network and propagated among nodes .

Q: What is the mempool and how do transactions get there?

A: The mempool (memory pool) is each node’s local cache of valid, unconfirmed transactions it knows about.When a user submits a transaction:

- The transaction is broadcast to nearby nodes.

- Nodes verify it (signature, no double spend, valid inputs, etc.).

- If valid and not yet in a block, nodes add it to their mempool.

Miners select transactions from their mempools to include in the blocks they attempt to mine .

Q: What is a block in the bitcoin blockchain?

A: A block is a batch of validated transactions plus metadata, chained to prior blocks via cryptographic hashes.Each block contains:

- A block header (version,previous block hash,Merkle root,timestamp,difficulty target,nonce).

- A list of transactions (starting with a special coinbase transaction).

Blocks are appended in sequence, forming the blockchain, which is an ordered, tamper‑evident history of all transactions .

Q: Who decides which transactions go into a block?

A: Miners decide.Each miner runs a full node that maintains a mempool. When constructing a candidate block,a miner:

- Selects a set of valid transactions from their mempool.

- Prioritizes by transaction fee rate (fee per byte/virtual byte) and other policies.

- Ensures the total block size/weight stays within protocol limits.

Different miners may choose slightly different transaction sets,but all must respect consensus rules .

Q: How are fees used to prioritize transactions for inclusion in a block?

A: Transactions include a fee: the difference between total input value and total output value. miners are economically incentivized to earn as much fee revenue as possible.They typically:

- Sort transactions by fee rate (satoshis per vbyte).

- Fill a block from highest fee rate to lowest, until reaching the block’s weight limit.

When the network is busy, users may raise fees to get faster confirmations, as higher‑fee transactions are more likely to be chosen earlier .

Q: What are the size and weight limits for a bitcoin block?

A: bitcoin uses a concept called ”block weight,” introduced with SegWit:

- Maximum block weight: 4,000,000 “weight units”.

- Roughly equivalent to about 1-2 MB of data, depending on the mix of legacy and SegWit transactions.

Miners must ensure the sum of transaction weights (including the coinbase transaction) does not exceed this limit when bundling transactions into a block .

Q: What is the coinbase transaction and why is it special?

A: The coinbase transaction is the first transaction in every block. It:

- Has no real inputs; instead it creates new coins (the block subsidy) according to the issuance schedule.

- Collects all transaction fees from the other transactions in the block.

The sum of newly created bitcoins plus collected fees is the miner’s block reward, sending value to an address they control. The structure and value of the coinbase transaction must follow protocol rules, especially the maximum allowed subsidy .

Q: How do miners build the transaction list for a candidate block?

A: The typical process is:

- Start with an empty candidate block template.

- Add a coinbase transaction with a provisional reward amount.

- Sort mempool transactions by fee rate.

- Iteratively add transactions, checking:

- All inputs are valid and not already spent within this candidate block.

- No consensus rules (size/weight, standardness rules) are violated.

- Stop adding when any further transaction would exceed block weight or other constraints.

- Recalculate the coinbase transaction’s reward to reflect the final fees included.

This list then becomes the block’s transaction section, and the Merkle root is computed from it .

Q: What is a Merkle tree and Merkle root, and how do they relate to bundling?

A: A Merkle tree is a binary hash tree built from all transactions in a block:

- Each transaction is hashed.

- Pairs of hashes are combined and hashed repeatedly until one root hash remains.

that final hash is the Merkle root, which is stored in the block header. It commits to the entire transaction set: changing any transaction changes the Merkle root, thereby invalidating the block header’s proof‑of‑work .

Q: How does proof‑of‑work link the transaction bundle to network consensus?

A: Once a miner has assembled a candidate block (including its transaction list and Merkle root), they:

- Construct the block header with the Merkle root and the hash of the previous block.

- Vary a nonce (and parts of the coinbase) to change the header’s hash.

- Repeatedly hash the header until finding a hash below the current difficulty target.

Finding such a hash is proof‑of‑work. The first miner to broadcast a valid block with sufficient work, and a valid transaction set, has their block accepted by honest nodes and added to the longest‑work chain .

Q: What role do full nodes play when a new block is broadcast?

A: when a node receives a new block, it independently verifies:

- The block header’s proof‑of‑work and linkage to the previous block.

- The validity of the coinbase transaction and reward amount.

- Every included transaction (signatures, no double spends, script validity, etc.).

- That block size/weight and other protocol rules are respected.

If valid, the node:

- Adds the block to its local blockchain.

- Removes the block’s transactions from its mempool.

Thus, nodes collectively enforce the rules that govern how transactions are bundled into blocks .

Q: Why might a valid transaction remain unconfirmed for a long time?

A: Common reasons include:

- Low fee rate: Miners prioritize higher‑fee transactions; low‑fee ones stay in mempools longer.

- Network congestion: During heavy activity, available block space is limited relative to demand.

- Policy filters: Some nodes/miners may temporarily exclude transactions that don’t meet their policy (e.g., very small outputs or non‑standard scripts), even if those transactions are technically valid.

Such transactions usually confirm once congestion eases or if they are replaced with higher‑fee versions (via mechanisms like Replace‑by‑fee) .

Q: How often are new blocks, and thus bundles of transactions, created?

A: bitcoin targets an average of one new block approximately every 10 minutes. The actual interval varies randomly because proof‑of‑work is probabilistic. The mining difficulty is adjusted roughly every two weeks (every 2,016 blocks) to keep the average interval near 10 minutes, irrespective of changes in total network hash power .

Q: How does this bundling process support bitcoin’s security and decentralization?

A: bundling transactions into blocks, secured by proof‑of‑work and verified by decentralized nodes, provides:

- Immutability: Altering a past transaction would require re‑doing the work for that block and all subsequent blocks.

- Consensus: The longest‑work chain defines the canonical transaction history.

- Resilience: No central party selects or censors all transactions; many miners and nodes participate, following common, open rules .

This combination is why bitcoin is often described as “open‑source, peer‑to‑peer money” with a collectively managed ledger .

Concluding Remarks

Understanding how transactions are gathered, validated, and committed to blocks closes much of the gap between using bitcoin and truly knowing how it effectively works. By seeing that miners are not just “creating coins” but packaging verified transactions into cryptographically linked blocks, it becomes clear why bitcoin can function securely without a central authority .

Each step in the process-from transaction propagation across the peer‑to‑peer network, to inclusion in the mempool, to eventual confirmation in a mined block-contributes to the robustness and auditability of the ledger. This same mechanism underlies the trust users place in balances, payments, and ultimately in the market value bitcoin commands on open exchanges .

With a solid grasp of how transactions are bundled into blocks, you are better equipped to interpret confirmation times, fees, and network conditions-and to understand why the blockchain structure remains central to bitcoin’s design and ongoing resilience.